Artinian Modules

Instead of the ascending chain condition, we can take its reverse.

Definition.

Let M be an A-module. Consider the set

of submodules of M, ordered by inclusion, i.e.

if and only if

. We say M is artinian if

is noetherian.

The ring A is said to be artinian if it is artinian as a module over itself.

Again M is artinian if either of the following equivalent conditions holds.

- Every non-empty collection of submodules of M has a minimal element.

- If

is a sequence of submodules of M, then

for some

.

Examples

Let . This is a noetherian ring as we saw; it is not artinian because we have a decreasing sequence of ideals

.

Let as a

-module where

. Then M is artinian but not noetherian (exercise). We thus see that an artinian module is not finitely generated in general.

Exercise A

1. Prove that in an exact sequence of A-modules:

,

M is artinian if and only if N and P are. In particular, the direct sum of two artinian modules is artinian.

2. Prove that if M is a noetherian A-module, any surjective linear is also injective. State and prove the dual statement for an artinian module.

Decide if each of the following statements is true.

3. The product of any two artinian rings is artinian.

4. Any quotient of an artinian ring is artinian.

5. Any localization of an artinian ring is artinian.

Simple Modules

Let A be a fixed ring throughout this article and M be an A-module.

Definition.

M is said to be simple if it is non-zero and has no submodules except 0 and itself.

We immediately have the following.

Lemma 1.

M is simple if and only if

for some maximal ideal

.

Proof

(⇒) Pick a non-zero and consider the A-linear map

,

. Its image is a non-zero submodule of M so it is the whole M; hence f is surjective. We have

and submodules of M correspond to ideals of A containing ker f. Thus ker f is maximal.

(⇐) Submodules of correspond to ideals of A containing

. Thus M is simple ⟹

is maximal. ♦

Example

Thus we see that simple modules over a coordinate ring k[V] (k algebraically closed) correspond to points on V. Even though we have as k-algebras, different points correspond to different A-modules!

Easy Exercise

Prove that for any ideals of A,

as A-modules if and only if

.

Composition Series

Next we would like to “factor” a module into its constituents comprising of simple modules.

Definition.

A composition series for M is a sequence of submodules

such that

is simple for all

. The length of the composition series is n; the composition factors of the series are the isomorphism classes of

, treated as a multi-set.

Example

Let and

be varieties cut out by the equations

and

respectively.

Recall that their scheme intersection (exercise D here) has coordinate ring

by Chinese Remainder Theorem. In fact, the above are all isomorphisms as algebras over where we have identified

with

. Thus we have the following composition series

This has length 3; the composition factors are two copies of and one copy of

.

Proposition 1.

M has a composition series if and only if it is a noetherian and artinian module.

Proof

(⇒) Suppose is a composition series. Each

is simple hence both artinian and noetherian. By induction one shows that all

are noetherian and artinian.

(⇐) Conversely suppose M is both noetherian and artinian; we may assume . If M has no simple submodule, we can find an infinitely decreasing sequence of submodules

, contradicting the fact that M is artinian. Hence we pick any simple submodule

. If

we are done; otherwise, we repeat the process with

and obtain a simple submodule

. This gives the next term for a composition series

, etc. Since M is noetherian, the process must eventually terminate. ♦

Corollary 1.

If M has a composition series, so do any submodule and quotient module of M.

Uniqueness of Composition Series

Theorem 1.

Let M be a noetherian and artinian A-module. The composition factors of any composition series are unique up to isomorphism and reordering.

Note

For a composition series we write

for the multi-set of its composition factors.

Proof

The proof is by contradiction; say a module is bad if it has two composition series with different sets of composition factors.

Step 1: Assume M is minimal.

Take the collection Σ of all bad submodules of M. Since M is artinian, we can replace M by a minimal element of Σ. Thus M has two composition series

such that ; and no other submodule of M has this property.

Step 2: Consider the easy case.

Clearly so

. If

then by minimality this is a good module so

and

have the same composition factors, a contradiction.

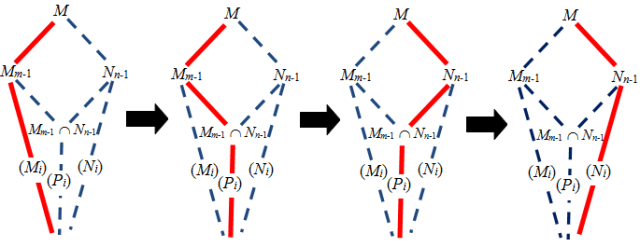

Step 3: Do the “diamond argument”.

Otherwise we have which gives us

and similarly .

Step 4: Apply induction.

Pick any composition series for

. Using (P) to denote the isomorphism class of a module P we have:

The second and fourth equalities follow from the fact that and

are not bad, since M is a minimal bad module. The third equality follows from step 3. In diagram form we have the following.

This completes our proof. ♦

Corollary 2.

If M is a noetherian and artinian module, write

(length of M) for the length of any composition series of M. This is a well-defined value.

Similarly, we can define the composition factors of M and denote it by

.

Note that if is an exact sequence of A-modules and M has finite length, then

This gives another application of short exact sequences.

Exercise B

1. Compute the length and composition series of

as an B-module.

2. Prove that for a ring quotient , a B-module M is noetherian (resp. artinian) as a B-module if and only if it is so as an A-module.

In the next article, we will look at artinian rings. It turns out this is a small subclass of the collection of noetherian rings.

Optional Note

All the results in this section can be generalized to left modules over a non-commutative ring. This has applications in representation theory, since a simple module over the group algebra (k = any field) corresponds to an irreducible k-representation of G.

It is possible for a non-noetherian ring to have a noetherian spectrum. For example if

It is possible for a non-noetherian ring to have a noetherian spectrum. For example if