Minkowski Theory: Introduction

Suppose is a finite extension and

is the integral closure of

in K.

In algebraic number theory, there is a classical method by Minkowski to compute the Picard group of (note: in texts on algebraic number theory, this is often called the divisor class group; there is a slight difference between the two but for Dedekind domains they are identical).

We will only consider the simplest cases here to give readers a sample of the theory.

Minkowski’s Lemma.

If a measurable region

has area > 1, then there exist distinct

such that

.

Proof

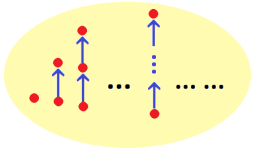

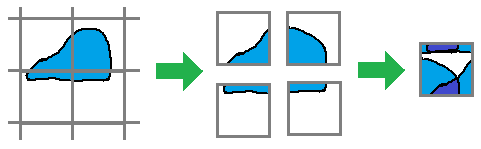

Use the following picture:

Since the area > 1, there exist two points which overlap in the unit square on the right. The corresponding then give

. ♦

Minkowski’s Theorem.

Let

be a measurable region which is convex, symmetric about the origin and has area > 4. Then X has a lattice point other than the origin.

Proof

Take , which has area > 1. By Minkowski’s lemma, there exist distinct

such that

. Since X is symmetric about the origin replace y by –y (so

) to give

. And since X is convex,

. Finally since

,

is not the origin. ♦

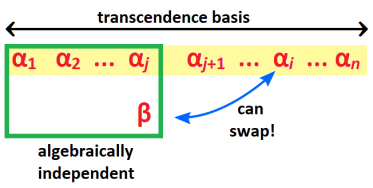

By applying a linear transform to we obtain the more useful version of Minkowski’s theorem.

Minkowski’s Theorem B.

Take a full lattice

(i.e. discrete subgroup which spans

). Taking a basis

of L, we obtain a fundamental domain

of area D. If

is convex, symmetric about the origin, and has area > 4D, then X has a non-zero point of L.

Picard Group of Number Rings

Now we use this to compute for

.

First note that any non-zero ideal has finite index since if

, then

is a non-zero integer in

so

, where N is the norm function. We let

.

Recall that if , by proposition 4 here, the composition factors of

comprise of exactly

copies of

for each i, so

In particular, for any non-zero ideals

, and we can extend the norm function to the set of all fractional ideals of A.

Exercise

Prove that if then

so we can consider as an extension of the norm function to the set of ideals.

To apply Minkowski’s theorem B, we identify with

. Let

be any non-zero ideal with norm N, considered as a full lattice in

. We take

where t will be decided later. Note that S is convex, symmetric about the origin and has area . If

where

then Minkowski’s theorem B assures us there exists

with

. Since this holds for all

we have:

Now has norm

, i.e.

. Hence every element of Pic A can be represented by an ideal

of norm 1 or 2. Since A has norm 1 and

has norm 2, we have proven:

.

More generally, one can show the following.

Theorem.

Let

be a finite extension. Then the Picard group of

is finite; its cardinality is called the class number of K.

Exercise

Prove that has class number 3. Note that

.

Prove that has class number 1.

Prove that has class number 2.

[ Hint: identify with

. Pick the square

for a suitable t. You could also pick

but it is not as efficient. ]

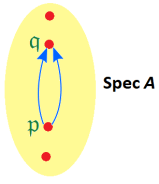

Geometric Example: Elliptic Curve Group

Take the elliptic curve E over given by

and let

be its coordinate ring. In Exercise B.1 here, we showed A is a normal domain. Clearly it is noetherian. By Noether normalization theorem,

. Hence, A is a Dedekind domain.

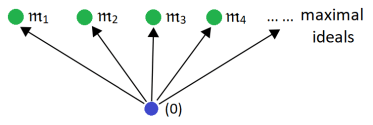

We will show how computation of Pic A leads to point addition on the elliptic curve. For each maximal ideal , write

for its image in Pic A. Recall that points

correspond bijectively to maximal ideals

.

Lemma 1.

Suppose

is not a unit. Then taking

as a complex vector space,

if and only if

can be represented by a linear function in X, in which case

for some

.

Note

The intuition is that the curve and the elliptic curve cannot have less than 3 intersection points (with multiplicity) unless we take a vertical line.

Proof

Since in the ring A, without loss of generality we can write

for . The condition

implies

and

have at most two intersection points. Solving gives us

.

If , the LHS has odd degree while the RHS has even degree; hence the equation has at least 3 roots and each corresponds to at least one point on the elliptic curve. If

and

, then

so

is linear in X, and we are done. ♦

Exercise

If we replace by a general algebraically closed field k, would the proof still work? What additional conditions (if any) need to be imposed?

Corollary 1.

No maximal ideal of A is principal.

Proof

If is generated by f then

, which is impossible by lemma 1. ♦

Corollary 2.

For any points

and

on E,

is principal if and only if

When that happens, we write

.

Proof

(⇐) If then setting

gives

If , this ring has exactly two maximal ideals, corresponding to maximal ideals

and

of A. If

, it has exactly one maximal ideal so we still have

.

(⇒) If is principal, then

so by lemma 1, f can be represented by a linear function in X so we must have P and Q as described. ♦

Corollary 3.

If

satisfy

, then

.

Proof

Let as in corollary 2. Then

. By the given condition

so by corollary 2 again we have

and hence

. ♦

Lemma 2.

For any

with

, there is a unique

such that

Proof

First suppose so P and Q have different x-coordinates. Let

be the equation of PQ. We get:

which has complex dimension 3. Since is divisible by

we have

for some

. Geometrically R is the third point of intersection of PQ with E, which can be equal to P or Q.

If with

, we can similarly pick a line through P of gradient

. Then as above

where

has a double root for

(this requires some algebraic computation). Hence

for some

. ♦

Summary.

The Picard group of A is given by

.

In particular it is infinite.

However, even in a catenary ring A, not all maximal prime chains may be of the same length. The reason is rather simple: A can have multiple minimal prime ideals and multiple maximal ideals. The catenary condition does not specify that every saturated prime chain from every minimal prime to every maximal prime must be of the same length.

However, even in a catenary ring A, not all maximal prime chains may be of the same length. The reason is rather simple: A can have multiple minimal prime ideals and multiple maximal ideals. The catenary condition does not specify that every saturated prime chain from every minimal prime to every maximal prime must be of the same length.