Skew Diagrams

If we multiply two elementary symmetric polynomials and

, the result is just

, where

is the concatenation of

and

sorted. Same holds for

However, we cannot express

in terms of

easily, which is unfortunate since the Schur functions are the “preferred” basis, being orthonormal. Hence, we define the following.

Definition. A skew Young diagram is a diagram of the form

, where

and

are partitions and

for each

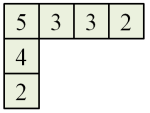

E.g. if and

then

Note that the same skew Young diagram can also be represented by where

and

These two Young diagrams are considered identical.

Definition. A skew semistandard Young tableau (skew SSYT) is a labelling of the skew Young diagram with positive integers such that each row is weakly increasing and each column in strictly increasing. Now

is called the shape of the tableau and its type is given by

where

is the number of times

appears.

E.g. the following is a skew SSYT of the above shape. Its type is (4, 1, 1, 1).

Skew Schur Polynomials

Definition. The skew Schur polynomial corresponding to

is given by:

where

is

. E.g. the above diagram gives

The proof for the following is identical to the case of Schur polynomials.

Lemma. The skew Schur polynomial

is symmetric.

Indeed, one checks easily that the Knuth-Bendix involution works just as well for skew Young tableaux.

So the number of skew SSYT of shape and type

is unchanged when we swap

and

Example

For and

, we have:

The following result explains our interest in studying skew Schur polynomials.

Lemma. The product of two skew Schur polynomials is a skew Schur polynoial.

For example, we have:

It remains to express as a linear combination of

, where

Littlewood-Richardson Coefficients

Recall that we have Pieri’s formula , where

is summed across all diagrams obtained by adding

boxes to

such that no two are on the same column. Repeatedly applying this gives us:

where and

is obtained from

by adding

boxes such that no two lie in the same column. Hence, the number of occurrences for a given skew Young diagram

is the number of skew SSYT’s with shape

and type

Example

If and

, here is one way of appending 4, 2, 1 boxes in succession:

which corresponds to the following skew SSYT:

This gives us the tool to prove the following.

Theorem. For any

with

, we have:

so the linear map

is left adjoint to multiplication by

Proof

It suffices to prove this for all where

Since

is the basis dual to

, the LHS is the coefficient of

in expressing

in terms of monomial symmetric polynomials. By definition of

, this is equal to the number of skew SSYTs with shape

and type

; we will denote this by

the skew Kostka coefficient.

By the reasoning above, when is expressed as a linear combination of Schur functions, the coefficient of

is also

. Since the Schur functions are orthonormal, we are done. ♦

Note

The theorem is still true even when does not all hold, if we take

. Indeed, by reasoning with Pieri’s rule again, every Schur polynomial

occuring in

must have

for all

Definition. When we express:

the values

are called the Littlewood-Richardson coefficients.

By the above theorem, this equals One can calculate this using the Littlewood-Richardson rule, which we will cover later.

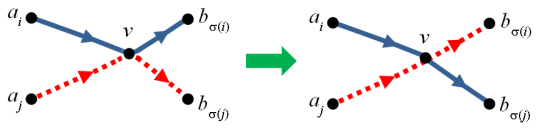

However, the involution

However, the involution

In the above diagram a → b means that b can be expressed as a polynomial in a with integer coefficients; the same holds for dotted arrows but now the polynomial may have rational coefficients.

In the above diagram a → b means that b can be expressed as a polynomial in a with integer coefficients; the same holds for dotted arrows but now the polynomial may have rational coefficients.