Motivation and Definition

While studying analysis, one notices that many important concepts can be defined in terms of “open sets”. One gets the inkling that this concept is critical in forming our notions of continuity, limits etc. In this article, we shall abstractise this further by considering only open sets. At first glance, it does seem rather unlikely that such a general definition could be useful in any manner. However, it will soon become clear that abstractisation has the following advantages:

- It brings out the essence of proofs of theorems, by highlighting specific properties of an object which are critical to the proofs.

- The concepts can be applied to vastly different areas of mathematics, including for example, number theory, Galois theory, commuative algebra (in more ways than one!) etc, and have proven to be extraordinarily fruitful in furthering their study.

Enough talk, let’s begin. Let X be any set. As mentioned above, we wish to define a topology on it by stating what constitutes “open sets”.

Definition. Let

be the power set of X (i.e. set of all subsets of X). A topology on X is a subset

satisfying:

;

- if

, then

;

- if

is a collection of elements of T, then

.

If U is a subset of X belonging to T, we say U is an open subset of X. If C is a subset of X whose complement X-C belongs to T, we say C is a closed subset of X.

Some observations:

- The definition does not preclude the possibility that a subset can be both open and closed, so the terminology is a little unfortunate. For a quick motivation of why closed subsets are of interest, read here.

- By repeatedly applying intersection, one notes that if

are open, then so is

. In other words, a topology is closed under an intersection of finitely many terms, but not infinitely many terms in general (see the example of R later, where the intersection of all

is {0}, which is not open).

Note that we could also define a topology by stating what constitutes “closed subsets” of X. Thus:

are closed subsets of X;

- if

are closed subsets of X, then so

is closed;

- if

is a collection of closed subsets of X, then

is closed.

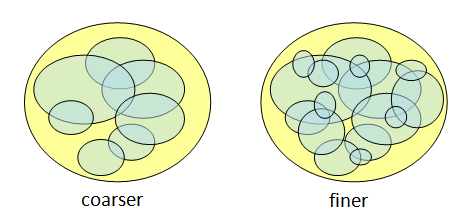

Definition. Suppose

are both topologies on X. If

, then we say

is a finer topology than

and conversely

is a coarser topology than

.

[ Note: this diagram is meant as an illustration of finer/coarser; it does not represent actual topologies. ]

Examples of Topologies

- On any set X, we have the discrete topology T = P(X) where every subset is open; this is the finest topology possible for X. Also, there’s the trivial topology

, which is the coarsest topology possible for X.

- Let

. The standard topology on X was already defined earlier. Recall that

is open if and only if for each x in U, there is an ε>0, such that any y in X satisfying |y – x|<ε must be in U also.

- Let X be a set. The cofinite topology is defined via having

open if and only if X–U is finite. In other words, the class of closed subsets is precisely the class of finite subsets, from which it’s clear that the cofinite topology satisfies the set of axioms of a topology.

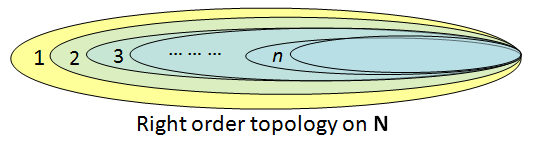

- Let N = {1, 2, … } be the set of positive integers. The right order topology on N is where the only non-empty open subsets are

for m=1, 2, 3, … . Note that

and

; the fact that the order topology is closed under arbitrary union follows from that every subset of N has a minimum.

- If

, where ∞ is just a dummy symbol here, then we can define a topology on N* by decreeing that the only non-empty open subsets are

Thus, any open subset containing ∞ contains all sufficiently large natural numbers.

[ Side note: more generally, one can define the order/right-order and left-order topology on any totally ordered set. Note that the right-order topology on N* differs from the one described in example 5, since {∞} is an open subset in the right-order topology. ]

[ Side note: more generally, one can define the order/right-order and left-order topology on any totally ordered set. Note that the right-order topology on N* differs from the one described in example 5, since {∞} is an open subset in the right-order topology. ]

Metric Spaces

Metric Spaces

One common source of topologies is via a metric function, which provides a geometry by indicating the “distance” between any two points in a set.

Definition. A metric on a set X is a function

such that:

- d(x, y) ≥ 0 for any x, y in X, with equality if and only if x=y;

- d(x, y) = d(y, x) for any x, y in X;

- d(x, z) ≤ d(x, y) + d(y, z) for any x, y, z in X (triangular inequality).

The pair (X, d) is then called a metric space.

The triangular inequality ensures that the function d behaves like a “distance function”.

Examples

- The discrete metric on any X is defined by d(x, y) = 0 if x=y and 1 otherwise.

- Let

. The Euclidean metric is the standard distance function

.

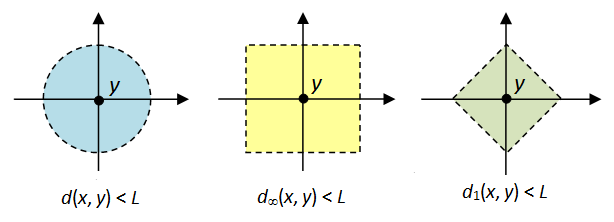

- Let

again. This time we take the metrics

and

. [ See diagram below. ]

- Let p be a prime number and X=Z, the set of integers. Given any integer m let

where

is the highest power of p dividing m; in the case m=0, since all powers of p divide m we have

. Then

is a metric, called the p-adic metric on Z. This was briefly alluded to in a prior post. [ Note: the triangular inequality follows from the fact that if

divides both x–y and y–z, then it divides x–z. One way of looking at this metric is that two integers are near if their difference is divisible by a high power of p. ]

- E.g. suppose p=5. Then d(5, 3)=|5-3|5 = 0, d(57, -18)=|75|5 = 1/25, and d(152, 27) = 1/125.

The following theorem shows that a metric space gives rise to a topology.

The following theorem shows that a metric space gives rise to a topology.

Theorem. Let (X, d) be a metric space. For x in X and ε>0, the open ball with radius ε>0 and centre x is defined by

We say that a subset

is open if for any x in U, there is an open ball

for some ε>0. Then the collection of open sets form a topology.

[ Note: the above diagrams for d, d1 and d∞ illustrate the open balls for the respective metrics. ]

Proof.

Clearly, and X are both open. Now, suppose

are open (in the sense of metric space). If

, then x lies in both U1 and U2. Thus, we can find

such that:

and

.

So .

Finally for arbitrary union of open subsets, let be open and

. If x lies in U, then it must lie in some Ui. Thus, for some ε>0,

. ♦

For example,

- the above metric space

induces the topology on Rn defined earlier;

- the discrete metric on any set X induces the discrete topology;

- the open ball N(x, ε) itself is an open subset of X (the proof is an exact replica of the one in an earlier post, by replacing |x–y| with d(x, y)).

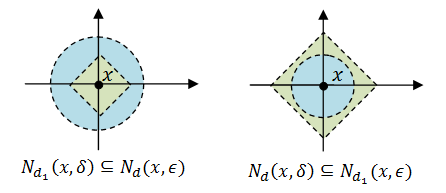

We say that a topology (X, T) is metrisable if there’s a metric d on X which induces it. But even if such a d exists, it is usually far from unique. For example, the above metrics d, d1 and d∞ on Rn all induce the same topology as we will show a short while later.

Definition. Two metrics d and d’ on X are said to be topologically equivalent if they induce the same topology.

Theorem. This happens if and only if:

- for any x in X and ε>0, there exists δ>0 such that

;

- for any x in X and ε>0, there exists δ>0 such that

;

[ Since there’re two metrics here, we use the subscript Nd to denote the open ball induced by d. ]

Proof

Suppose d and d’ induce topologies T and T’ respectively. It suffices to show that the first condition is equivalent to that T’ is finer than T.

For the forward direction, suppose , i.e. it is open in the metric space (X, d). Then for any x in U,

for some ε>0. By the first condition,

for some δ>0. Hence it follows that U is open in the metric space (X, d’) too.

For the converse, suppose let x be in U and ε>0. Then since is open in T, it is also open in T’. Hence

for some δ>0. ♦

For example, the following diagram shows that d1 and d are topologically equivalent on Rn.

Conclusion: every metric space induces a topology and many different metrics on the same space can induce the same topology. We’ll see later that some topologies are inherently non-metrisable.

Conclusion: every metric space induces a topology and many different metrics on the same space can induce the same topology. We’ll see later that some topologies are inherently non-metrisable.