Power-Sum Polynomials

We will describe how the character table of is related to the expansion of the power-sum symmetric polynomials in terms of monomials. Recall:

where exactly since

is not defined.

Now each irrep of is of the form

for some

; we will denote its character by

Each conjugancy class of

is also given by

where

and

has cycle structure

E.g. if

we can take

as a representative.

We will calculate the character value by looking at the characters of

For that, we need:

Lemma. If the finite group

acts on finite set

, then the trace of

is:

, the number of fixed points of

in

Proof

Taking elements of as a natural basis of

, the matrix representing

is a permutation matrix. Its trace is thus the number of ones along the main diagonal, which is the number of fixed points of

♦

Hence we have:

Theorem. Let

be the trace of

on

Expressing each

as a sum of monomials, we get:

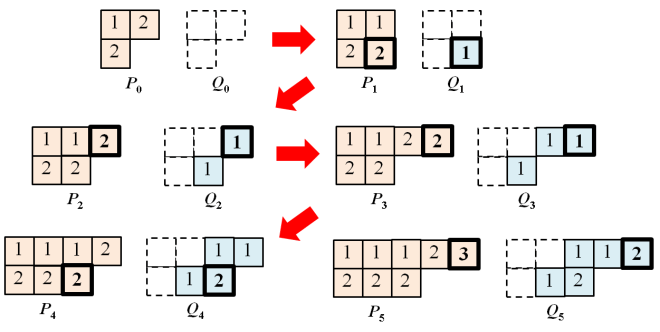

Proof

Let us compute the coefficient of in the expansion of

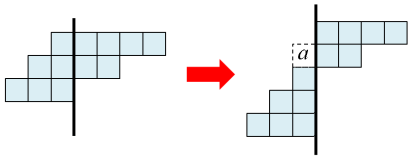

For illustration let us take

and

; pick the representative

To obtain terms with product

here is one possibility:

The corresponding fixed point is given by

and

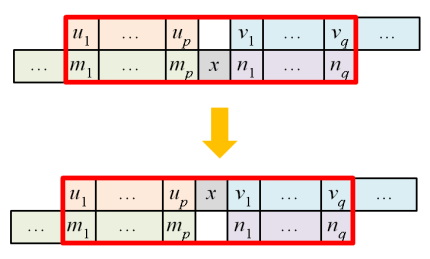

In the general case, each contribution of corresponds to a selection of:

such that

This corresponds to a partition defined by running through all the cycles of

and putting the elements of the c-th cycle into the set

for

Such a partition is invariant under

♦

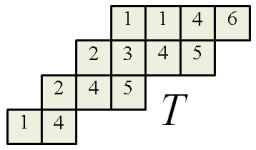

Example

Thus is the number of ways of “merging” terms

to form the partition

upon sorting. For example, taking

and

from above, the coefficient of

in

is 7:

Character Table

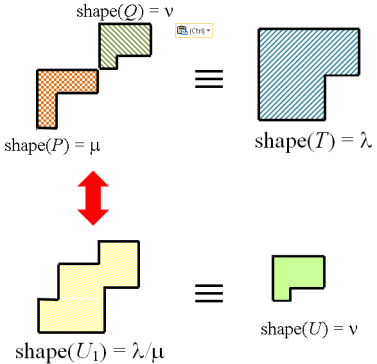

Writing the above vectorially, we have where

is the trace of

on

Thus, we have

which gives us where

so X is the transpose of the character table for

Hence, we have:

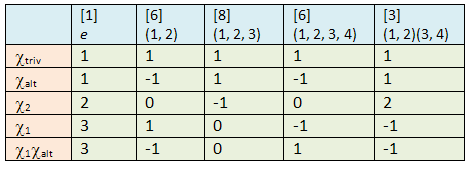

Example: S4

For d=4 we obtain:

where the rows and columns are indexed by partitions 4, 31, 22, 211 and 1111. One checks that is the character table for

:

Orthogonality

Finally, orthonormality of irreducible characters translates to orthogonality of power-sum polynomials.

Proposition. The polynomials

form an orthogonal set, and

is the order of the centralizer of any

with cycle structure

Proof

Since and the

are orthonormal,

which is entry of

. This is the dot product between columns

and

of the character table. By standard character theory, it is

where

is the conjugancy class containing

Now apply

♦

Under the Frobenius map, the power-sum symmetric polynomial corresponds to:

so